Between the local and the global. Identity of Polish folk art

Polish folk art today is situated between the local and the global. On the one hand, it is strongly connected with rural areas and rooted in local tradition. On the other hand, it undergoes dynamics of postmodern reality, becoming increasingly an element of popular and mass culture. Historical, social and political processes that have largely influenced its today’s reception are not without significance. The identity of folk art is influenced by ever-duplicated myths and stereotypes, which can be observed both in popular and research discourse. Many scholars also point to the end of folk culture and the inability to return to its original form. But in my dissertation I tried to perceive folk art as a living phenomenon, taking into account its dynamics and changeability.

The choice of this subject was dictated by the desire to draw attention to the areas of art that are outside the mainstream or on its border. I wanted to look at the direction in which folk art is going and what methods should be applied in research. Is it possible to look at folk art not only from the perspective of ethnography but also from the perspective of history of art? Are we able to go beyond established myths and stereotypes and abandon a classical vision of folk art? How does it position itself in relation to the mainstream art? Where are its boundaries, and finally, what makes a given artist a folk one?

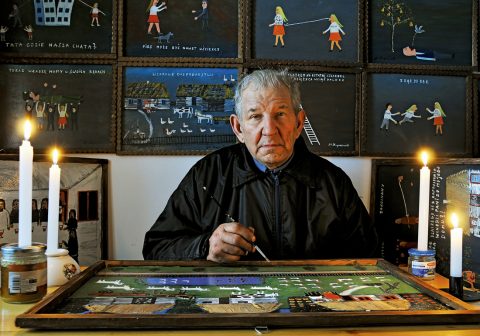

I started my research with historical contexts, paying particular attention to the influence of the People’s Republic policy and to the aspect of commercialization, the so-called folk for sale, which could be observed mainly due to operation of Cepelia Center of Folk and Artistic Industry. It was also important for me to use proper terminology as the notions used should involve critical reflection, and perhaps complete re-definition. I tried to characterize the image of today’s folk art on the basis of such artists as Elżbieta Świderek, Stanisław Koguciuk and Bogdan Ziętek, as well as activities such as embroidering The Battle of Grunwald and the participation of folk artists in the exhibition of Monika Drożyńska. I also looked at the Rural Housewives Association, the Folk Artists Association, and festivals, fairs and folk art markets, which, in addition to ethnographic museums, have become the main venue for the presentation of this art. Thus, they situate folk art within the tourism industry. No less important were the contexts of naive art, art brut, and outsider art, which often incorporate folk artists.

Due to the complexity and ambiguity of the phenomenon of folk art, it was important for me to take an interdisciplinary approach to the subject. I used the perspective of postcolonial studies and the aspects of the sociology of art, among others. It emphasized the fact that folk art is always considered in opposition to the official, high, elite art. And it is referred to as the weaker, the worse, or as an element of low culture. Moreover, the issues related to class divisions are clearly evident in this context. This is also related to the aspect of not working through a part of our history, as well as the category of memory that has become important in reading today’s art. Folk artists have often been treated as “Strangers” and “Others”. They remain in a weaker position due to the influence of the dominant culture. This is established not only in the popular opinion, but also among the artists themselves. On the other hand, the leading role of ethnography in the study of folk art makes the art aspect most often omitted, and its image is shaped by artificial preservation of tradition, relegating it to showcases and open-air folk museums. In contrast, language, stereotypes and myths that have established themselves around the countryside, as well as the entire folk culture, influence the image of the art described, sometimes becoming a tool of power and oppression. They create a picture that largely reflects our ideas about folk art, rather than actually expressing it.

The analysis of individual artists and works contributed to the definition of folk art in a broader context. It is difficult to determine its precise boundaries, so it is necessary to approach the related phenomena in a singular and individual way. It is worth to look at folk art also from the perspective of “bottom-up cultures” and the theory of possible worlds of art. This allows us to overcome the myths and patterns that have been established around it, and to stand up to the homogeneous vision of culture. As long as we read folk art only in reference to the country and tradition, it will always be presented in the context of ethnographic curiosity. So today, in order for folk art to emerge in the world of art, discursive practices should be sought, as well as places, individuals and institutions that would give it the status of art.

(born 1992)

Studies: history of art at the Faculty of History and Social Sciences of the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University (2011–2014) and at the Faculty of Visual Culture of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw (2015–2017). Internships at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Zbigniew Raszewski Institute of Theatre and Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Collaborated with Pracownia Duży Pokój. Currently intern at the Sammlung Zander Museum in Bönnigheim. She also works as a cultural manager in social and cultural projects.